I have been building a research plan on teachers’ professional learning in social networks (such as Kaikkialla.fi by the OmniSchool Project). The OmniSchool Project that develops learning environments with schools has been fortunate to participate in existing networks and support emerging networks. The research plan will focus on a very crucial question in terms of the “connected teacher”: what are the effects of Twitter networking on teaching practice and teacher thinking?

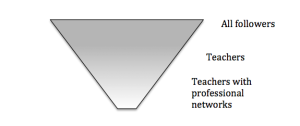

Figure. Filtering research participants for interviews.

Professionals spend more and more time on Twitter and other social network sites. They also see that this connects with their productivity (Microsoft survey 2013). Twitter allows instant idea and information sharing by users to their followers. A tweet is an expression of a moment or idea packed into 140 characters. It can contain text, photos, and videos, usually through a web link. Millions of tweets are shared every day.

The idea is to investigate the possible effects of social media use (like in Twitter) on professional learning and practice. The professional networks will be analyzed through social network analysis. Among other interesting things, this will reveal the teachers who just hold an account on Twitter, or use it for other personal purposes and those teachers who are actually networking professionally (see Figure above).

The plan is to first analyze teachers’ professional connections and networks and process those into a graph. Social network analysis allows contacts and interactions to be analysed easily and fast. The special interest is in the types of online connections and networks that exist between teachers and out-of-school actors. The second part of the research plan focuses on the teachers’ practical reasoning and its relations to professional social networking (in Twitter). The possible effects on practice are analyzed on a micro level at schools. The data will be collected with the stimulated recall interview method (STR), i.e. interviews that make use of the video recordings of teacher’s lessons. The data analysis combines practical argument analysis and data-based content analysis of the interviews.

The research proposal includes a comparative element between Finland and New Zealand. A foreign research context equivalent to the OmniSchool initiative is The Mind Lab by Unitec in New Zealand. The Mind Lab is an important investment to improve teachers’ professional skills and practical knowledge related to learning in the digital age. Their model of in-service training is very different to what is traditionally used in Finland as well as the model that has been developed in the OmniSchool Project (Learning Festival, in Finnish Oppimisfestivaali). Although the research remains descriptive in nature, it will be very interesting to see whether the teachers who are professionally active online also reflect on how student learning should be organized in the digital age.

I will defend my PhD at the Faculty of Behavioural Sciences on April 29, 2011. What will I defend then? I think there are some important thoughts that are already presented by other (media) educationalists, too. Here are my ideas about these issues.

I will defend my PhD at the Faculty of Behavioural Sciences on April 29, 2011. What will I defend then? I think there are some important thoughts that are already presented by other (media) educationalists, too. Here are my ideas about these issues.